wednesday, December 11, 2019

This is a story of broken dreams, of young athletes who become imprisoned by silence, under the hold of a coach. They are traumatised children, who no longer dare run, swim or enter into combat. They number hundreds of victims, powerless in the face of the code of silence, the denial and the abandonment of the so-called embracing family that is the world of sport.

There are hundreds of cases in France of young female athletes who complain of being victims of sexual violence, walled in silence with their dreams of reaching the podium shattered, who can no longer run, swim or compete, and who find themselves powerless in face of the omertà, denial and ignorance of sports bodies.

Over a period of eight months, Disclose has investigated the issue of sexual violence in the world of French sport. This foray into the closed world of amateur and professional clubs reveals the ineptitude of a whole system to deal with the problem, from sports associations, federations and even the public authorities.

- 77 cases

- 28 sports

- 276 victims

Beginning in the 1970s and up to the present day, Disclose can reveal 77 cases involving at least 276 victims, most of them aged under 15-years-old at the time of the events. The cases involve 28 different fields of sport, including football, gymnastics, athletics, as well as archery, roller-skating and chess.

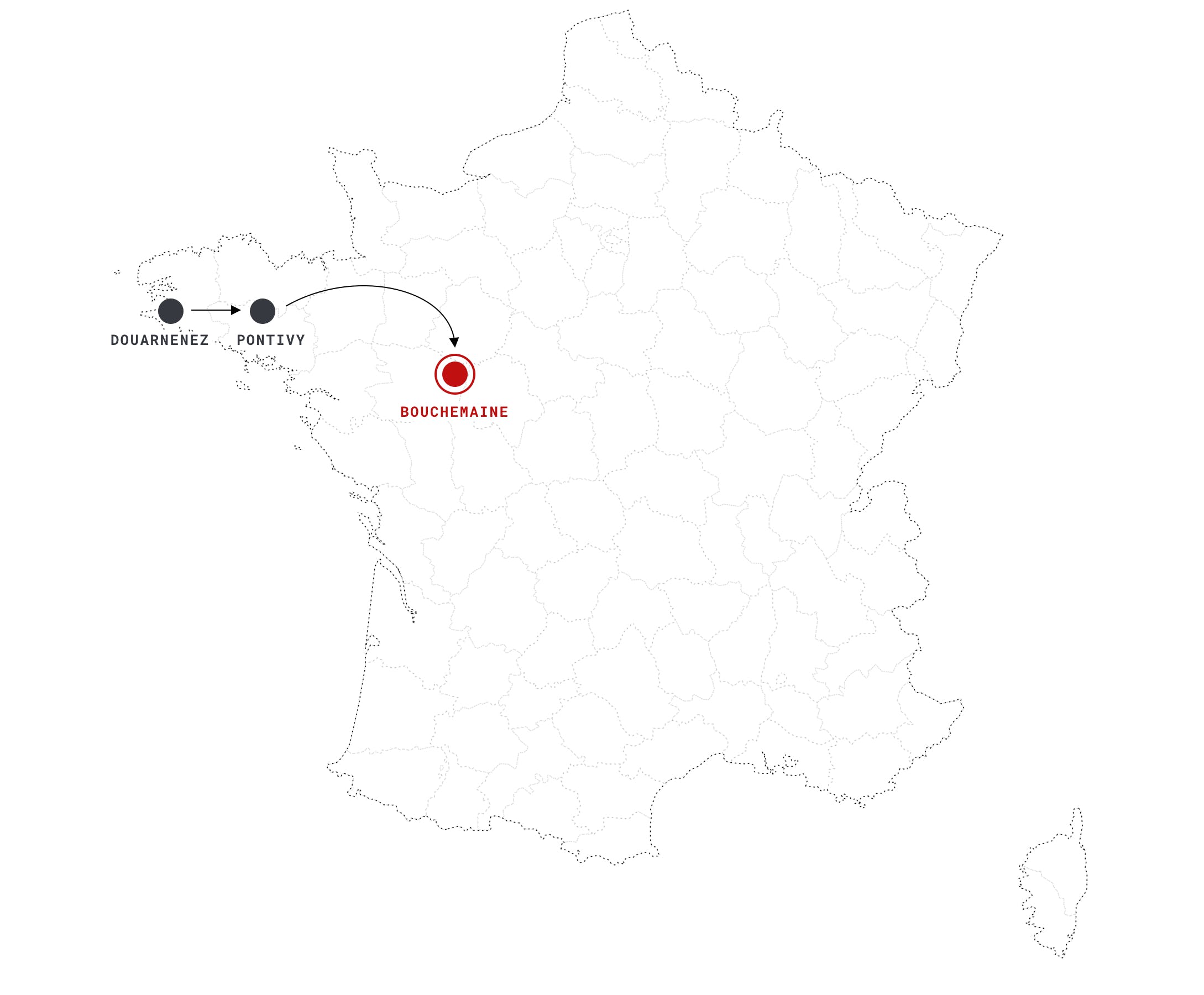

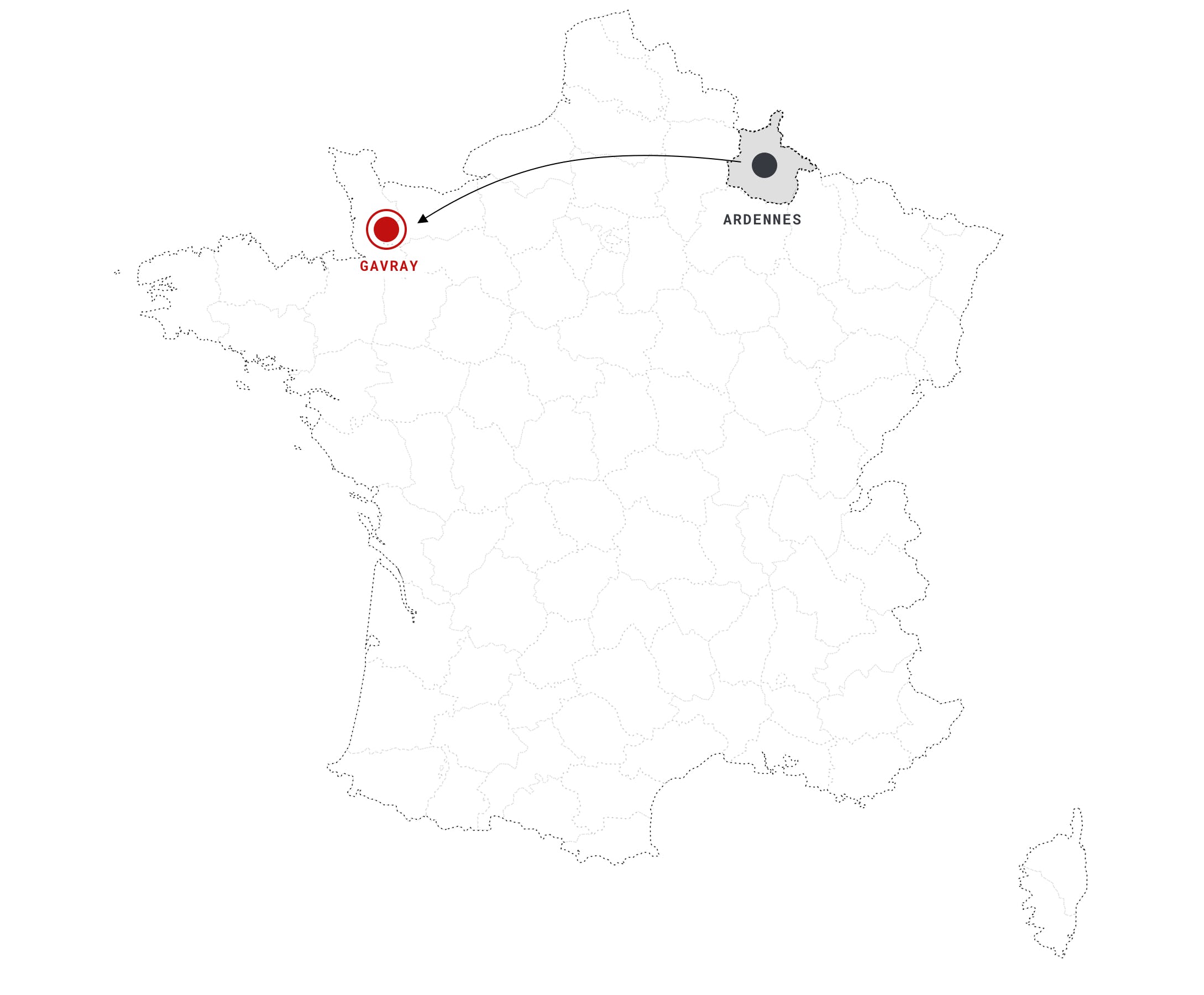

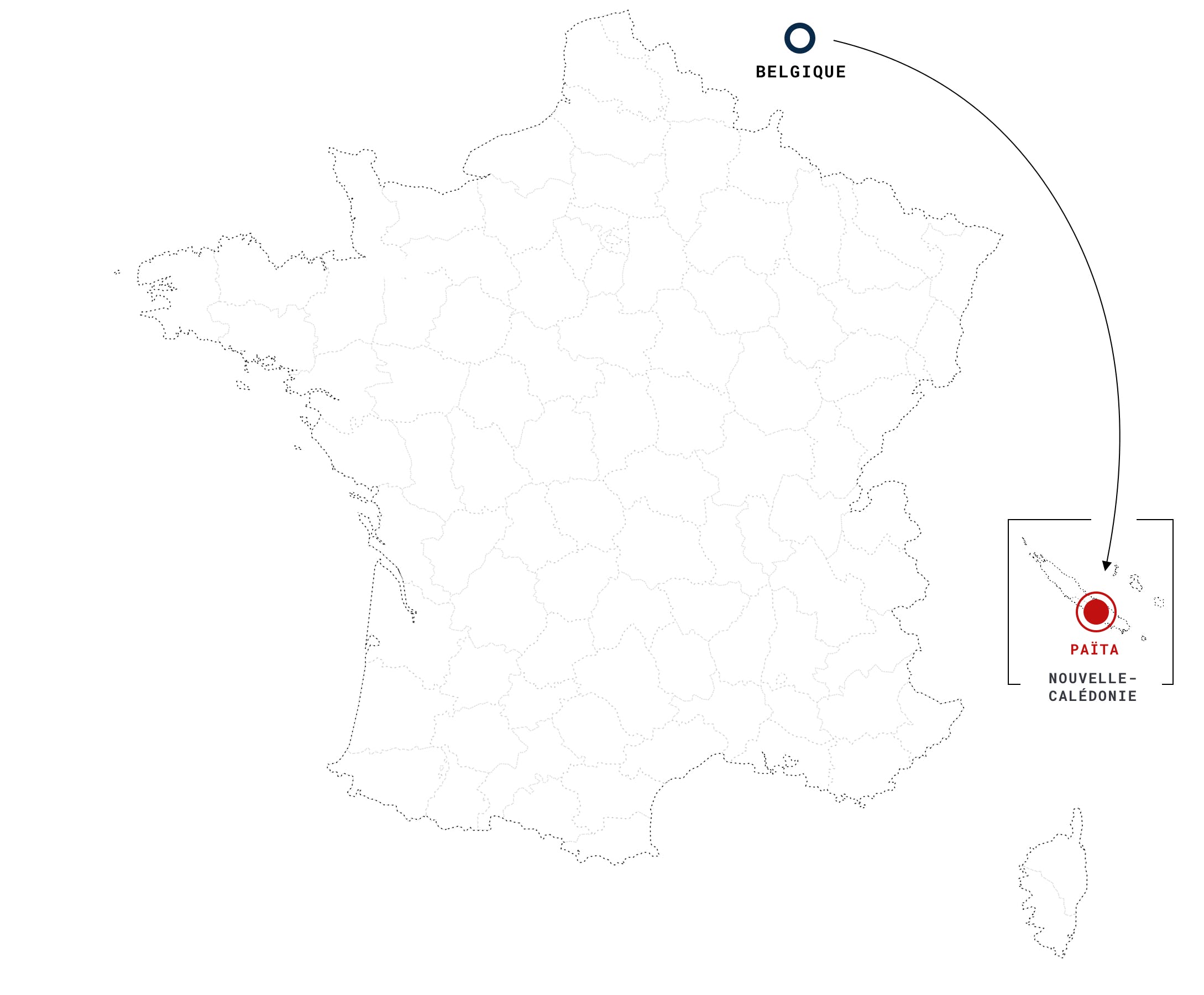

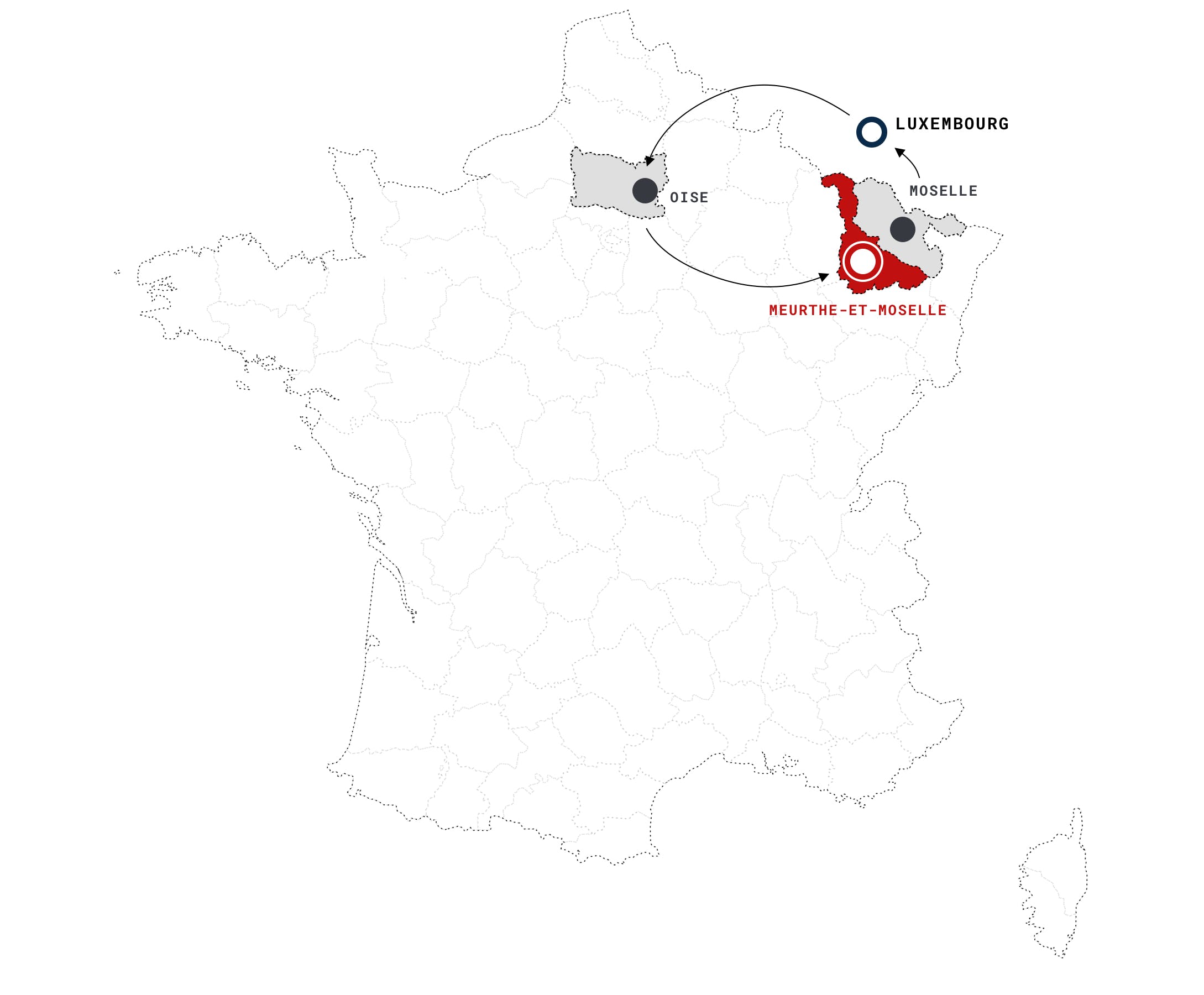

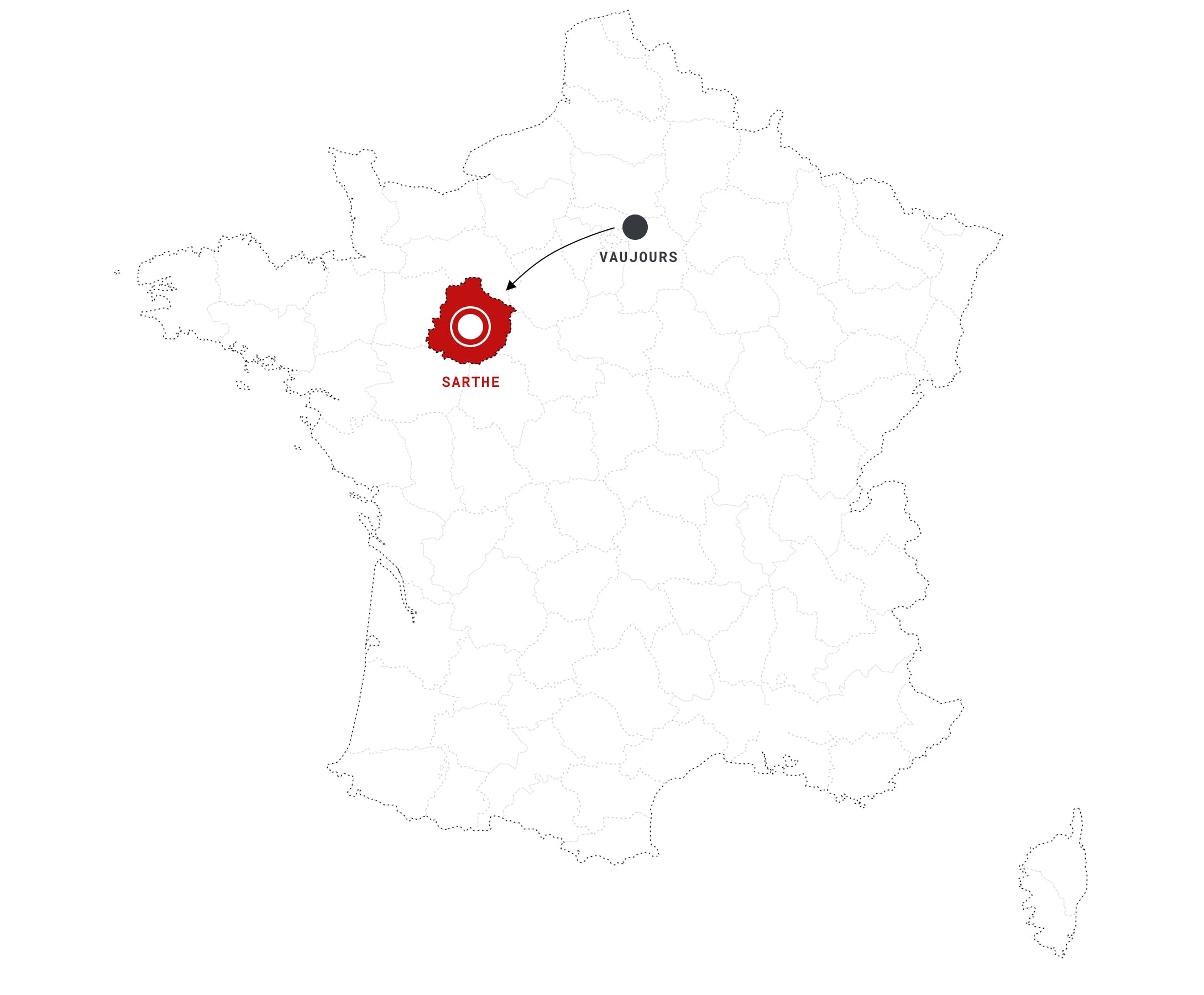

THE 77 CASES ACROSS FRANCE

Zoom out see French overseas territories

In the research behind the cartography published here, Disclose contacted hundreds of alleged victims of sexual violence in sports activities across France, and witnesses to the events they describe. They include accounts that are revealed here for the first time, and which were thoroughly counter-checked against legal papers, internal documents and press cuttings, all of which were compiled into a data base.

They unveil major failings by clubs and federations, local and national public authorities, and the justice system. These include the absence of a system of control of voluntary sports teachers, instances where suspected perpetrators who are under investigation were allowed to continue in their activities, the lack of monitoring of sexual delinquents, the inaction of officials and sports bodies that choose to cover up scandals rather than to defend the interests of the athletes in the field, flouting the laws in place.

THE VICTIMS

Disclose chose to focus on those cases that illustrate one or more of the following elements: repeat offending, the continued activities of a convicted person as a sports instructor, the failure to alert the competent authorities after an alleged offence has been reported, efforts to defend the perpetrators, and negligence in situations where there are strong indications of wrongdoing.

Repeat offending

One of the first of the alarming statistics to emerge from this investigation by Disclose calls into question the justice system’s monitoring of sexual delinquents. In the data compiled, almost one in every two cases of sexual crime in the context of sports activities involved repeat offending. The definition of repeat offending used here is that of a repetition of events of a sexual character, using the common description of this and not that employed in strict legal terminology (see more in the sidebar below “Background”). These cases include both remunerated and voluntary sports instructors.

Concerning the latter, there is no legal or administrative requirement to check whether a person who applies to train or lead a sports club on a voluntary basis has a criminal record, nor to verify if their name features on the list compiled by the French justice authorities of people convicted of a violent or sexual crime (the FIJAISV).

Regarding cases of repeat offending involving salaried or otherwise remunerated self-employed instructors, these are often characterised by the failure to carry out a check of criminal records or the validity of the professional card of sports instructor – and even the striking off by the justice system of certain convictions on criminal records (see more in the accompanying report “The scourge of coaches who are repeat offenders”).

Kept in the job

Another alarming statistic is that in 78% of the sexual assault cases identified, either the alleged perpetrator was kept in their job despite an ongoing investigation, or a convicted perpetrator regained a post. It is a situation that increases the danger of a repeat offence. Yet under the law, according to Article 212-9 of the sport code – the laws and decrees that regulated sports activities – a person who has been convicted of an offence of a sexual nature cannot be allowed to train athletes or have a role of responsibility in a sports activity (see more in the accompanying report “Sexual abusers who remain in post”). It is legislation that sports managers are all too often little aware of.

The failure to alert authorities

In 18 affairs, representing a quarter of the victim cases identified, individuals or institutions were informed of detailed events but failed to inform the justice authorities, despite being required to do so by law. In the majority of cases, those responsible for this code of silence were never called to account for having covered up offences of a sexual nature (see more in the accompanying report “The culpable silence of the authorities”).

Running away

![]()

Athlétisme

De Saint-Brieuc à Angers

Un entraîneur de lancer du javelot est condamné à Saint-Brieuc pour avoir agressé sexuellement trois jeunes filles d'un club d'athlétisme breton dans les années 1990. En 2010, des athlètes d'un club d'Angers l'accusent des même faits mais il est relaxé pour "doute".

In almost a quarter of affairs investigated here, there were 18 cases where perpetrators either moved to another club or another geographical region. In a system where the communication of information is easily interrupted, such movements offer a manner of passing ‘under the radar’. In the majority of the above cases, the movement was followed by repeat offending.

Support for the perpetrator

In 18 affairs, the club, federation, local authorities or the school gave support to the perpetrator. In those cases, the complaints of the victims were often disregarded, and in some there were attempts to intimidate the victim. Convictions or other judicial sanctions were sometimes placed in question, and even described as judicial errors.

Neglecting serious warning signs of behaviour

Disclose has identified nine affairs in which behavioural warning signs – which did not always involve events that could be regarded as criminal – that preceded a sexual assault were dealt with lightly. Examples of behaviour such as a coach spending a night alone together with an athlete in their hotel room, or taking a shower, naked, among child players of a club should be reported to the authorities according to the recommendations of child protection professionals, including police services and associations.

There are numerous examples of those who failed their responsibilities, allowing sexual delinquents to slip through the net. In 53% of cases, the failings are on the part of the justice system. This raises a number of questions. How is it, for example, that someone convicted of sexual offences against minors is not systematically prohibited from subsequently exercising an activity with children? Why does social and judicial follow-up of cases sometimes only last for a few years? By what criteria is the decision made, and in some cases very rapidly, to strike off sexual offences from criminal records?

Then comes the role of the clubs, which are at the origins of the mishandling of 35 percent of the cases investigated by Disclose. These reveal how information about sexual misconduct is not automatically passed on to sports federations, the police or the justice authorities, often in an attempt to protect the club from scandal. Furthermore, sports managers, whether occupying a voluntary position or a professional post, only rarely receive training on how to deal with sexual violence or to instruct them on the details of the law on the subject. The result is that they find themselves quite helpless when a case occurs in their midst.

There are examples in which local town halls, schools and the employers of sports instructors were informed of events but subsequently failed to alert the authorities. Article 40 of the French criminal code requires elected representatives and public employees to inform the justice authorities when they have knowledge of a suspected crime. In two cases investigated by Disclose, it was the public administration services – the sports ministry and a local prefecture – which demonstrated culpable inertia.

Finally, there are cases where the families of victims are reluctant to speak out. One of the reasons can be a notion of owing a certain loyalty towards a sports instructor. “In the Church, one talks of there being a moral hold [over people], but it’s the same in sport,” commented French Senator Marie Mercier, the rapporteur of a fact-finding commission of inquiry into sexual crimes against minors established by the parliamentary upper house in 2019.

In comparison to media reporting in France of cases of paedophilia that have disgraced the Catholic Church, those of sexual violence in the world of sport have received very little coverage. Yet two French sportswomen who were victims of sexual violence notably sounded the alarm several years ago: one was the athlete Catherine Moyon de Baecque, in the early 1990s, and the other was tennis woman Isabelle Demongeot, in 2005. But their stand was largely in vain.

In 2008, the then French sports minister, Roselyne Bachelot, presented a plan to crack down on sexual violence and harassment in sport. That led, one year later, to the publication of the results of a nationwide inquiry into the issue which found that 17 percent of those athletes questioned said they were victims of, or believed themselves to have been subjected to, some form of sexual violence. Over the following ten years, successive sports ministers have produced statements and grand PR campaigns on the issue, but to little effect.

In November 2017, as the #MeeToo movement prompted by unfurling allegations of sexual assault against US film producer Harvey Weinstein gained full momentum, the then French sports minister, Laura Flessel, a former Olympic gold medallist in fencing, gave an interview in which she claimed that “there is no code of silence in sport” regarding sexual violence.

This investigation by Disclose demonstrates the contrary.